An embryologist explains: Embryo freezing

Nadia De Rosa, Embryologist and Deputy Lab Manager for Adora Fertility Sydney shares the science behind the scenes when it comes to freezing embryos.

For patients undergoing IVF treatment our goal is to create embryos. With scientific advancements it is common for more than one embryo to be created in a treatment cycle. We need to understand which embryos have the best chance of successfully creating a pregnancy, and this is done by allowing the embryos to develop in culture for 5-6 days after fertilisation has occurred. On day 5 and 6 we expect to see embryos reach the blastocyst stage of development. Usually the best quality embryo is selected for fresh transfer, and if other embryos have also formed good quality blastocysts embryologists can freeze them for the future.

Deciding which embryos are suitable for freezing requires a visual assessment. During this assessment the embryologists grade the embryo based on its developmental stage and quality. Only viable embryos that we believe are able to survive the freeze and thaw process are frozen. If you would like to know more about how embryos are graded please read How Embryos are Graded.

How embryos are frozen

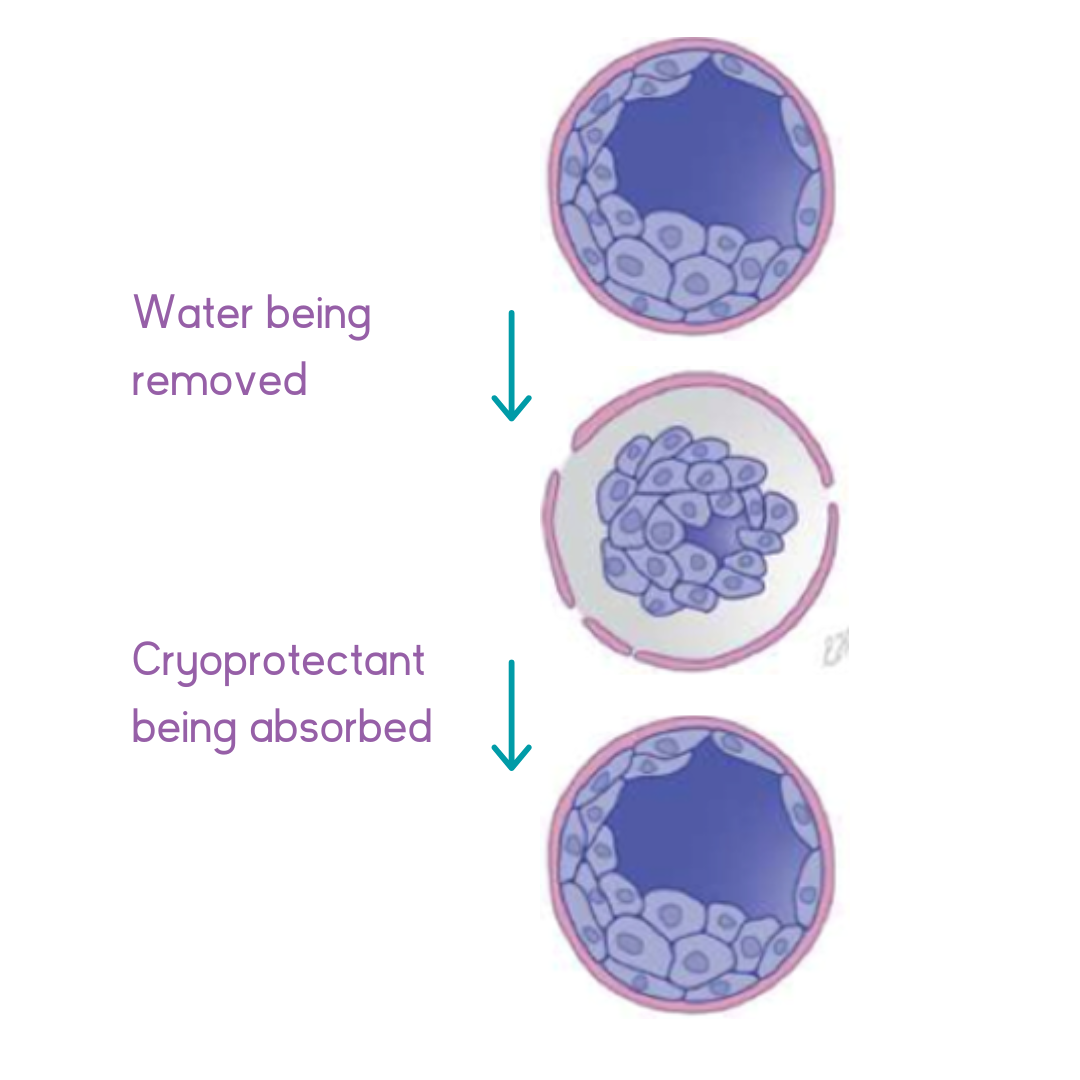

Embryologists freeze embryos using a process called “vitrification”. For successful freezing we need to protect the embryos from the cold temperatures of liquid nitrogen (-196oC). This is done by removing any water from the embryo and replacing it with a concentrated solution called cryoprotectant. Water must be removed to prevent the formation of ice crystals within the cells of the embryo. Part of this process results in the embryo collapsing as the fluid filled cavity is replaced with cryoprotectant.

The embryo is then plunged into liquid nitrogen. During this process, the temperature of the embryo plummets from room temperature (25⁰C) to -196⁰C within a second and the embryo forms a glass like solid. Once an embryo is frozen it is kept within liquid nitrogen in a storage tank until required for future treatment. Due to the extremely cold temperature the embryo quality and viability does not deteriorate over time, which allows embryologists to store embryos for many years until they are needed for treatment.

How embryos are thawed

When embryologists thaw embryos, it is the reverse process. The cryoprotectant is removed and the water is replaced back into the embryo. The embryo will collapse again before re-expanding back to its original volume, which may take serval hours to fully complete.

Why freeze embryos?

Freezing embryos can be useful to many patients. Embryos may be frozen for fertility preservation or to reduce the likelihood of ovarian hyper-stimulation syndrome. We often freeze embryos for our patients who have produced more than one embryo so that in the future they do not need to have another egg collection procedure.

Embryologists only freeze good quality viable blastocysts that are likely to survive the process of freezing and thawing. This means that frozen embryos have a high chance of survival for future treatment – at Adora Fertility the embryo survival rate is >95%. It is also important to know that success rates following the transfer of a frozen embryo are similar to success rates with fresh embryos.

References

- Edgar, D. H., Bourne, H., Speirs, A. L., & McBain, J. C. (2000). A quantitative analysis of the impact of cryopreservation on the implantation potential of human early cleavage stage embryos. Human reproduction (Oxford, England), 15(1), 175–179.

- Kader, A. A., Choi, A., Orief, Y., & Agarwal, A. (2009). Factors affecting the outcome of human blastocyst vitrification. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, 7, 1-11.

- Kuwayama, M. (2007). Highly efficient vitrification for cryopreservation of human oocytes and embryos: the Cryotop method. Theriogenology, 67(1), 73-80.

- Sciorio, R., Tramontano, L., Campos, G., Greco, P. F., Mondrone, G., Surbone, A., Greco, E., Talevi, R., Pluchino, N., & Fleming, S. (2024). Vitrification of human blastocysts for couples undergoing assisted reproduction: an updated review. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology, 12, 1398049.